Originalism vs Living Constitution: Jill Lepore’s Warning

To push, “If you believe in the American Constitution, you believe that people have the right to draft especially. Today we will discuss about Originalism vs Living Constitution: Jill Lepore’s Warning

Originalism vs Living Constitution: Jill Lepore’s Warning

In recent years, constitutional debates in the United States have become more intense, more divisive, and more consequential. At the heart of many disputes is how we are to interpret the U.S. Constitution: should its meaning be fixed (or largely fixed) according to the intentions or understandings of its framers (“originalism”)? Or should it be considered a living document, whose meanings evolve with social, technological, moral, and political change (“living constitution” theory)?

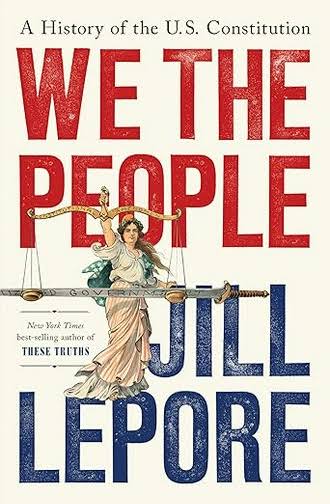

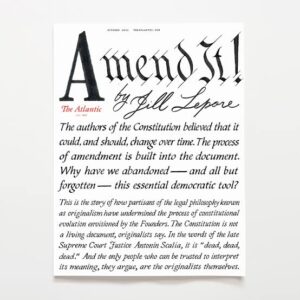

Harvard historian Jill Lepore has recently entered this debate with penetrating arguments and historical scholarship in her much-anticipated work We the People: A History of the U.S. Constitution (2025). Lepore issues a warning: the dominance of originalism is eroding the Constitution’s capacity to evolve, to respond to justice demands, and even to maintain its legitimacy. This article explores her warning, outlines the two interpretative camps, surveys historical and current challenges, and considers whether Lepore’s alternative—the “philosophy of amendment”—offers a viable path forward.

What Is Originalism? What Is the Living Constitution?

Before delving into Lepore’s critique, we need to define terms.

Originalism is the legal philosophy that the Constitution’s meaning was fixed at the time of its adoption. Proponents differ on sources (framers’ intention, public meaning, textual original meaning, etc.), but they typically emphasize historical documents like the Federalist Papers, ratification debates, the intentions or understanding of the framers, etc.

Living Constitution (or “living constitutionalism”) holds that a constitution must be construed in light of evolving values, social practices, and contemporary understandings; that its terms are necessarily general, and that interpretation should consider present-day contexts. Critics of originalism often invoke this theory.

These approaches are not merely academic; they shape court decisions, public policy, rights, and civic trust.

Jill Lepore’s Warning: Core Claims

Jill Lepore’s recent work contributes a serious historical, legal, and moral critique of the dominance of originalism. Her warning can be broken down into several interlinked claims:

Originalism undermines the amendability of the Constitution

The U.S. Constitution was designed with Article V to allow amendments—a mechanism for change without violence. Lepore emphasizes this “philosophy of amendment” as central to the framers’ design.But the actual practice of amendment has grown rare; since the Bill of Rights and early wave of amendments, only 27 amendments have been ratified, despite tens of thousands of proposals.

Rigid originalism substitutes judicial interpretation for democratic change

Because amendment has become so difficult, Lepore argues, many policy and social changes once pursued through constitutional amendment are instead routed through judicial interpretation. Courts, especially the Supreme Court, become arenas of contention over what was intended or originally meant. This concentrates power in judges rather than in people or representative institutions.Originalism’s historical sources are incomplete or selectively used

Lepore points out that much of what originalists rely upon—the framers’ writings, Madison’s notes, Federalist Papers, ratification debates—were not widely disseminated or definitive even at the time. Some records are fragmentary; many perspectives (especially those of women, enslaved persons, Native Americans) were excluded from formal constitutional decision-making, and their views remain marginal in originalist accounts.Originalism tends toward ideological uses and selective history

According to Lepore, many recent originalist arguments cherry-pick or ignore history that does not favor their preferred outcome. If history supports an outcome, it is embraced; if not, dismissed or treated as irrelevant. This risks turning history into a tool for ideology rather than scholarship.Loss of legitimacy and democratic engagement

When people feel that constitutional change is almost impossible, when judicial decision-making is seen as detached from democratic input, legitimacy suffers. Also, civic engagement can atrophy: citizens no longer imagine themselves as having power over constitutional structure—they await court rulings rather than participate in constitutional politics.

Lepore’s warning is not abstract: she sees concrete risks, including increased polarization, citizens losing faith in institutions, and a Constitution that becomes “frozen” when society around it shifts.

Historical Context: Amendment vs. Interpretation

To understand how we got here, Lepore traces constitutional history and how the tension between amendment and interpretation played out over time:

In early decades, amendments were more frequent. The Bill of Rights was ratified very soon after the original Constitution. Several key fundamental rights and structural changes were embedded via amendments (e.g. abolition of slavery, extension of voting rights). Lepore shows that early Americans viewed amendment as a normal tool of constitutional evolution.

Over time, proposals multiplied but success was rarer: thousands of amendments have been introduced, but only a few have been ratified. The amendment process requires high thresholds (2/3 in both houses of Congress or a constitutional convention, then 3/4 of states).

Parallel to this, judicial interpretation gradually assumed more importance: courts interpreted clauses regarding free speech, privacy, equal protection, etc., often reading meanings into the Constitution that framers did not explicitly foresee. Sometimes courts relied on originalist tools (for instance, historical understanding), sometimes not. Lepore notes that in recent decades originalism has become more popular among conservative legal scholars and jurists.

Lepore describes modern America as having “one of the lowest amendment rates in the world,” and for decades no major amendment has succeeded. Meanwhile, litigants seek rights not by amending but by gaining favorable court rulings.

Originalism: Strengths and Weaknesses

Originalism has its attractions and its strengths. But Lepore argues that its weaknesses are serious, especially in the current political and social climate.

| Aspect | Strengths of Originalism | Weaknesses / Critiques (from Lepore and others) |

|---|---|---|

| Predictability & Stability | By anchoring the meaning of constitutional text in its historical meaning, originalism promises stability and constraint, limiting judges’ discretion. | However, historical records are partial, contested, and often exclude voices; multiple plausible understandings may exist, leading to less predictability than originalists claim. Also, strictness can block needed change. |

| Limits Judicial Activism | Originalism aims to prevent judges from reading in their own preferences, restraining the judiciary. | In practice, originalism’s proponents have made arguments which seem to mirror their policy preferences; it can give cover to decisions that are deeply value-laden yet justified by selectively chosen historical sources. Lepore argues that originalism is sometimes a way to mask ideological judicial activism under the guise of fidelity. |

| Respect for Founders & Text | Allows respect for the Constitution’s authors and for democratic legitimacy in their intentions. | But founders were products of their time, with many flaws (e.g. slaveholding, exclusion of women, Native Americans, etc). To treat the original moment as normative for all time can perpetuate injustices. Also, originalist sources were not always widely known or applied in early U.S. history. |

| Checks on Judicial Power | Poses constraints: text, structure, history limit how far courts can stretch the Constitution. | Yet, in many cases, courts already interpret with reference to current values (e.g. equal protection, due process) even under “originalist” rulings; and when history is unclear or unhelpful, originalism provides tools for judges to choose among competing interpretations — thus discretion remains. Lepore suggests that originalism in practice is not as constraining as its proponents suggest. |

| Adaptability / Justice | Less focus on adaptability; originalism tends to resist changes not concretely foreseen in history. | Underweighting adaptability is dangerous when moral, technological, or social understandings change (for instance, rights for women, issues like abortion, equality, sexual orientation, privacy, digital rights). If constitutional interpretation can’t keep pace, either law becomes archaic or rights suffer. Lepore argues that rigid originalism may make change nearly impossible outside the courts. |

The Living Constitution: Strengths, Critiques, and Lepore’s Perspective

Let’s similarly look at the living-constitution approach, which Lepore generally supports (though with nuance), to see what it offers and what challenges it faces.

Strengths:

Adaptability & Relevance

It allows constitutional law to respond to societal changes: new technologies, social norms, evolving notions of equality and justice. Without that, laws rooted in eighteenth- or nineteenth-century understandings could become unjust. Lepore argues that framers themselves recognized need for amendability.Inclusiveness & Recognition of Disadvantaged Voices

The living constitution perspective tends to pay greater attention to groups historically excluded — women, people of color, Native Americans, enslaved populations. Lepore shows how their constitutional engagement, though often invisible, has shaped constitutional possibility.Legitimacy & Democratic Engagement

When citizens feel that constitutional change is possible (via amendment, popular participation, etc.), the Constitution does not feel like a closed artifact controlled entirely by judges. This contributes to democratic health. Lepore warns that when change appears impossible, citizens might disengage or lose trust.Practical Governmental Function

Many modern issues were not foreseeable in 1787: digital privacy, environmental degradation, biotechnology, etc. A living approach gives legal interpreters room to address challenges authorities could not anticipate.

Critiques / Potential Weaknesses:

Risk of Judicial Overreach

If constitutional meaning is too flexible, judges may imbue the text with contemporary values in ways that overstep what is democratically accountable. Critics worry that living constitutionalism can become whatever a majority of judges want it to mean.Lack of Constraint / Predictability

For law to function, people (including courts, legislators, citizens) need some stability and predictability. If the Constitution is read in accordance with shifting values, what counts as constitutional rights or requirements may change unpredictably.Potential for Undermining Rule of Law

If constitutional norms are too fluid, there is risk of retrospective reinterpretation or instability in legal expectations. Also, frequent overturning of precedents can erode legal certainty.Democratic Legitimacy

Some argue that interpretive flexibility should be accompanied by democratic input; otherwise, judges become de facto lawmakers. The need for legitimacy remains central.

Lepore’s Philosophy of Amendment: A Middle Path?

One of the central contributions of Lepore’s recent work is her articulation of what she calls the “philosophy of amendment.” This is not simply the living constitution doctrine; it is a reminder that the Constitution itself supplies mechanisms for change, that the framers saw amendment as foundational, and that respecting those mechanisms (and restoring their usefulness) is vital.

Key aspects:

Amendability as legitimacy: Lepore argues that a constitution that cannot be changed is at risk of losing moral and political legitimacy. If citizens cannot imagine fixing injustices by democratic constitutional means, faith in institutions erodes.

Restoring the amendment process: Because Article V has become almost dormant due to the high bar for amendment and increased political polarization, Lepore warns that reliance on judicial interpretation alone is unsafe. She suggests we need reforms (or at least serious thought) to help make constitutional amendment once more a viable route.

Looking beyond classic framers’ sources: Part of Lepore’s project is to “widen the lens” in constitutional history, to include voices ignored or marginalized, to consider what was happening outside formal constitutional convention settings—women’s conventions, Black political organizing, etc.—as constitutive of constitutional possibility even if they were not formally recognized. Awareness and inclusion of those alternative constitutional histories helps challenge a narrow originalism.

So, Lepore’s philosophy is not to abolish originalism entirely but to re-balance the constitutional order so that amendment and democratic constitutional engagement are central, not peripheral.

Case Studies & Current Implications

To see Lepore’s warning in action, we can look at some recent or ongoing controversies.

Supreme Court appointments and ideological leanings

With an originalist majority, the Court has in recent years revisited prior precedents (e.g. on abortion). Because amending the Constitution is so difficult politically, much of the battle over rights is fought in the Courts rather than legislatures. This gives enormous power to justices—life-tenured, less directly accountable to the public. Lepore warns this is a dangerous dependency.The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA)

ERA is a dramatic example of how democratic and popular energy for change can be blocked by constitutional mechanics. Though ERA was widely discussed in 20th century and had broad support, its amendment has stalled. Lepore shows that even widespread agreement does not overcome structural obstacles in the amendment process.Polarization and deadlock

As parties become more politically polarized, consensus required for constitutional amendment becomes harder to attain. Article V’s supermajority requirements were designed to demand broad agreement; but when political division is deep, such agreement is nearly unattainable. Without reform, the Constitution risks becoming static despite changing public moral understandings.Technological, social, and moral change

Issues like digital privacy, gender identity, environmental protection, biotechnology, racial justice, etc., pose questions not anticipated by the 18th- or 19th-century framers. If originalism is overly strict, the Constitution might fail to provide fair legal responses. The living constitutional view, supported by Lepore, invites constitutional interpreters and democratic actors to find ways to adapt.

Critically Assessing Lepore’s Warning

Lepore’s historical scholarship is rich and her arguments are powerful, but her case is not without critics or challenges. Some critical perspectives:

Feasibility of Amendment Reform: Making constitutional amendment easier or more functional is politically difficult. Supermajorities, time, and state ratification were intentionally made hard to prevent capricious or trending changes. Relaxing these may open the way to instability or capture by well-organized narrow interests.

Judicial Power and Separation of Powers: Some argue that heavy reliance on judicial interpretation threatens the separation of powers: judges are not elected, and lifetime tenure means their decisions may reflect their own philosophical or ideological orientations rather than democratic will. The challenge is: how to ensure adaptability without over-empowering judges?

Tensions within Living Constitutionalism: The living-constitution approach itself has multiple versions. What counts as moral/social evolution? Who decides? Sometimes one side accuses the other: “you are using ‘living constitution’ to get what you can’t win at the polls”—a critique of legitimacy. Lepore acknowledges some of these tensions; she doesn’t automatically endorse all judicial innovations, but warns about freezing.

Risk of Loss of Standards: As interpretations evolve, there is risk of lower standards of legal certainty. If precedents are too frequently overturned or if meanings shift too rapidly, individuals may not be able to rely on constitutional rights in the way they expect.

Implications and What Might Be Done

If we accept Lepore’s warning, what are the possible implications, what reforms or changes might help, and what obstacles stand in the way?

Possible Reforms

Constitutional Amendment / Reform Initiatives

Reforming Article V or related state procedures to reduce barriers. Examples might include lowering thresholds, easing ratification, expanding who may propose amendments, or giving greater weight to direct democratic participation.

More citizen initiatives for amendment; popular forums or constitutional conventions.

Broader Understanding of Constitutional Sources

Courts, scholars, and legal actors might expand historical sources to include more marginalized voices (women, enslaved people, indigenous communities, etc.), more informal constitutional politics (e.g. petitions, conventions outside the formal ratification process).

Legal education that incorporates constitutional history more broadly, not just framers’ documents.

Norms of Judicial Restraint Paired with Accessibility

Even within living constitutionalism, courts could develop norms of modesty: change through interpretation when necessary, but deferring where democratic or legislative approaches are possible.

Encouraging legislative and popular participation in constitutional reform rather than relying solely on courts.

Civic Education & Engagement

If citizens don’t believe constitutional change is possible, legitimacy suffers. Education that helps people understand amendment process, constitutional history, and their role in constitutional politics may foster stronger engagement.

Public forums, debates, media attention on constitutional reform.

Obstacles

Political Polarization: As noted, polarization makes the supermajorities required for amendment very hard to reach.

Inertia & Institutional Resistance: Institutions (Congress, state legislatures, courts) may prefer status quo or benefit from judicial rulings over constitutional amendments which require broad consensus.

Constitutional Rigidity Built In: Many parts of the U.S. Constitution are hard to change by design, to avoid frequent or whimsical amendments. Altering that risks unforeseen consequences.

Public Opinion & Ambiguity: Even when people favor certain rights or changes, opinions are often divided on how to constitutionalize them. Also, ambiguity about what “living constitution” means in practice can lead to distrust.

Conclusion: The Balance Between Stability and Change

Jill Lepore’s warning is that the constitutional order is in danger of becoming frozen—not by text alone, but by political, institutional, and interpretative practices that privilege originalism at the expense of democratic adaptability. Yet she does not argue for lawless or boundless living constitutionalism; rather, her philosophy of amendment seeks to restore balance: recognizing that amendments are integral, that history is contested, that the framers anticipated change, and that participation matters.

If the Constitution is to remain credible, just, and alive, then the challenge is to preserve its core commitments—rule of law, individual rights, separation of powers—while ensuring it can respond to evolving understandings of justice, identity, technology, and society. In Lepore’s view, letting originalism become the only game in town risks losing that capacity.

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

Average rating 0 / 5. Vote count: 0

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

About the Author

usa5911.com

Administrator

Hi, I’m Gurdeep Singh, a professional content writer from India with over 3 years of experience in the field. I specialize in covering U.S. politics, delivering timely and engaging content tailored specifically for an American audience. Along with my dedicated team, we track and report on all the latest political trends, news, and in-depth analysis shaping the United States today. Our goal is to provide clear, factual, and compelling content that keeps readers informed and engaged with the ever-changing political landscape.